A Serpent Down the Rabbit Hole

May 09, 2022

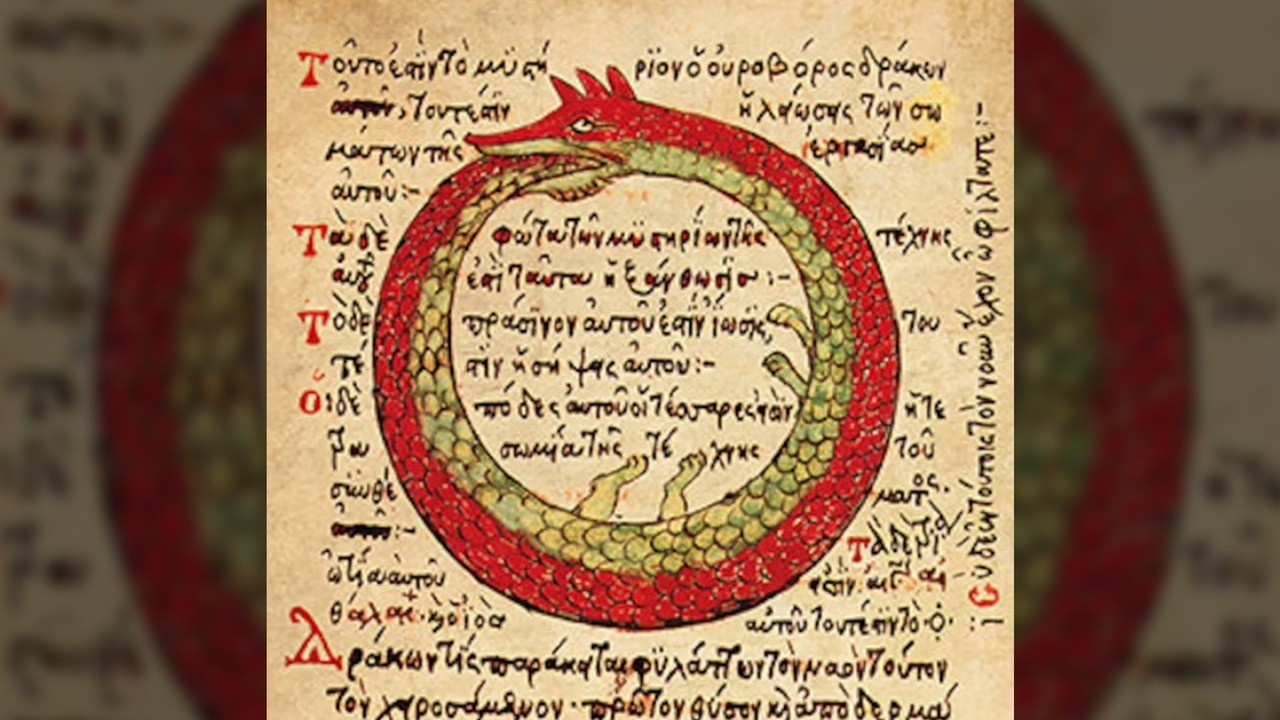

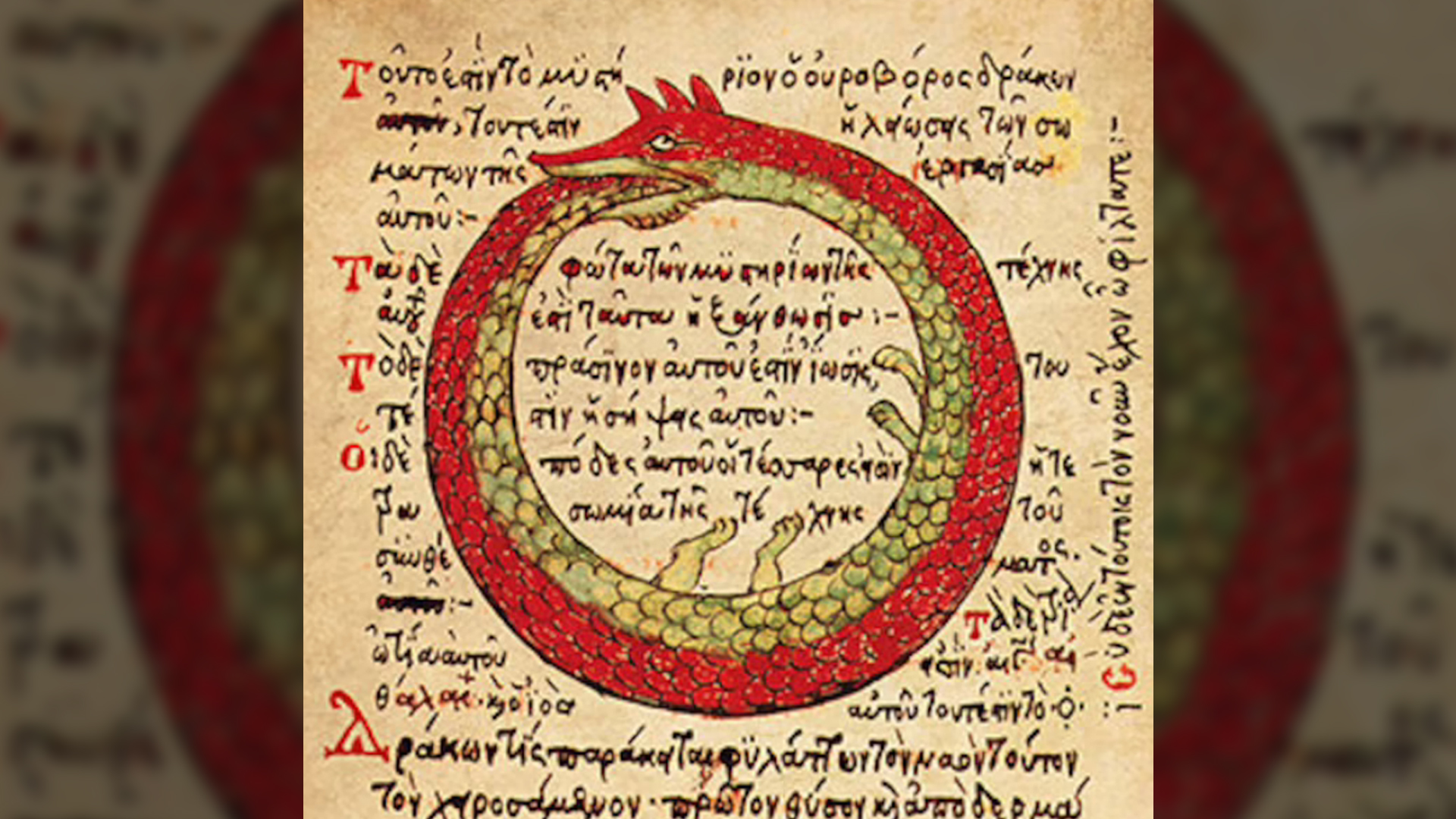

Alchemy. The word is derived from AL-KHEMET which originated in Egypt meaning “from the black land.” The oldest known allegorical symbol in alchemy, the ouroboros, also has its origins in Egypt, depicted on King Tutankhamun’s burial shrine (circa 1323 B.C.). At least that’s the earliest we have found to date. And this symbol, while with us for thousands of years, seems to have found renewed interest in today’s modern world. Apropos.

The ouroboros caught my eye some years back, or I should say ears, when viewing the film Predestination, starring Ethan Hawke and Sarah Snook. While I won’t spoil any of the twisted paradoxes within this savvy film based on the 1958 short story “All You Zombies” by Robert Heinlein, there were several references to “the snake eating its own tail” that scratched at the back of my mind, and I had to investigate further. Down the rabbit hole I went, exploring this esoteric and ancient symbolism.

The ouroboros represents the concept of eternity and endless return, as well as the unity of the beginning and end of time, creating an eternal cycle. This cyclical nature of our universe is one of renewal. As life dies it decays into the ground and grows again as new life. From the death of a solar system springs forth another. I touched on this a bit during my last blog article on the possibilities of a universe parallel to ours running in reverse time. Has our ancient symbolism always shown us what our science is now discovering... or rather, rediscovering?

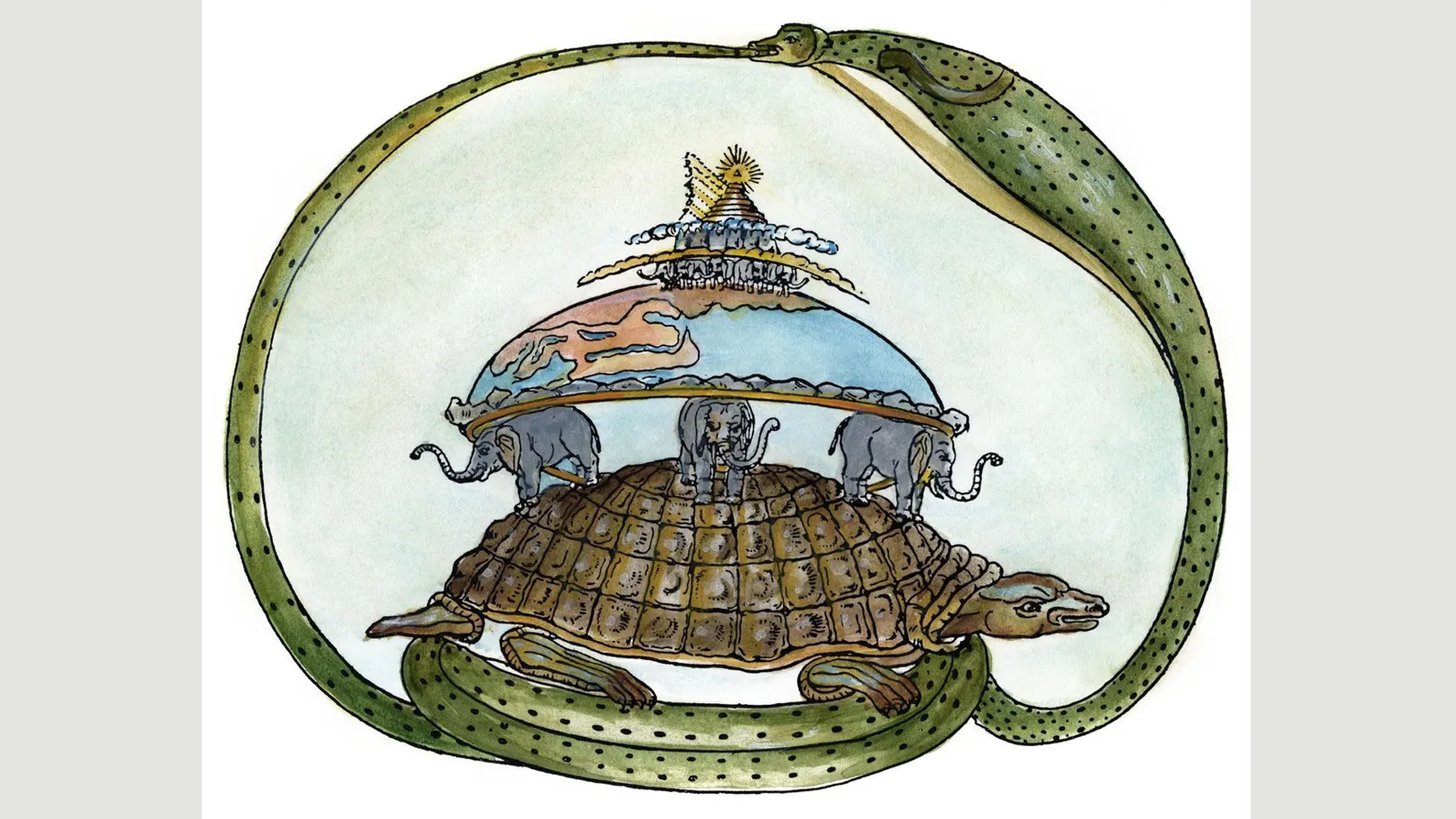

Not only do we see this iconography of the ouroboros in ancient Egypt, but we also see it in ancient Hindu traditions. In their depiction, a tortoise supports elephants upon whose backs the Earth rests. All of this is enclosed by the serpent Asootee.

However, the most recognizable representation of the ouroboros is probably that of the 1478 drawing by Theodoros Pelecanos. This drawing is contained within a manuscript Pelecanos produced now known as the Parisinus graecus 2327, which includes copies of texts from the 11th Century and other works of unknown origin, and is held within the Bibliothèque Nationale in France. The ouroboros drawing happens to be one of these copies but not from the 11th Century – it is much older, and is from a lost alchemical tract by Synesius, a Greek bishop of Ptolemais in ancient Libya, c. 373 – c. 414.

Welcome to the rabbit hole.

In 393 AD at the age of 20, Synesius traveled with his brother, Euoptius, to the city of Alexandria in Egypt, where he became an enthusiastic Neoplatonist and disciple of the legendary philosopher, Hypatia. Some years later in 398, he was chosen as an envoy to the imperial court in Constantinople but returned to Alexandria in 403 where he married before moving to Cyrene in Libya in 405. Although Synesius later became a Christian bishop, he maintained Neoplatonism roots and studied alchemy. His letters to Hypatia are the earliest known references to a hydrometer, a device used for measuring the relative density of liquids and is still used today. In fact, I use a hydrometer to measure the specific gravity of my wine during the winemaking process.

It certainly sounds like Synesius had quite an interesting life, but what does that have to do with the ouroboros aside from the fact he created an illustration of it? When we research and explore, we look for connections.

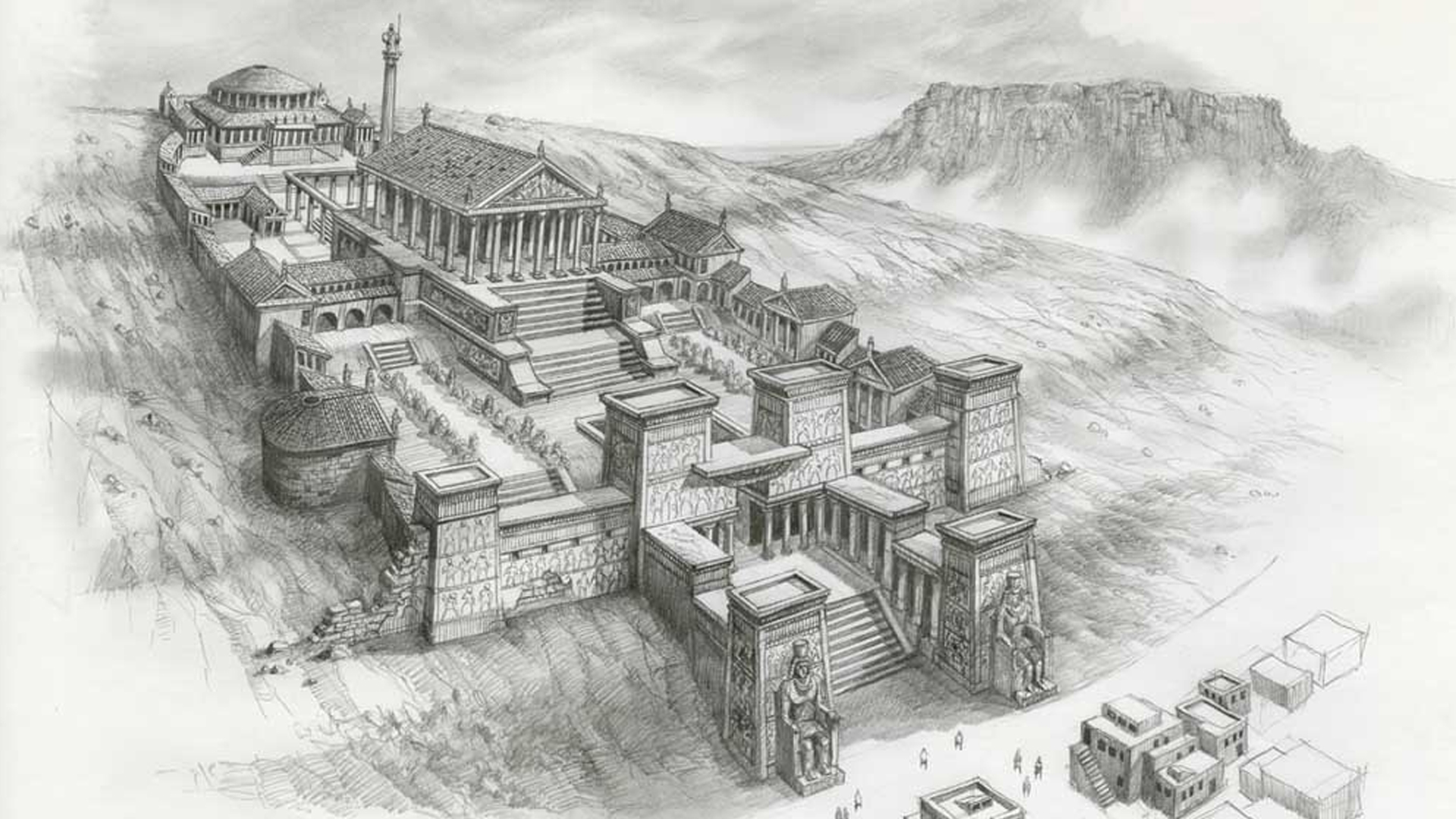

The famous destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria dates back to 48 BC, a casualty of war when Julius Caesar found himself trying the survive a civil war between Cleopatra and her brother, Ptolemy XIII. Under siege, Caesar set fire to Ptolemy’s fleet in the Alexandrian harbor, which gave him the upper hand, but this action had dire consequences. The fire spread into the city and consumed the Great Library.

All was not lost, however, The Great Library had a “daughter library” nearby in the Serapeum, a temple dedicated to the deity Serapis, which housed some remaining documents. The Serapeum endured for another four centuries, containing the largest collection of books in the city of Alexandria during that time, until it was destroyed by Theophilus in 391 AD.

During its time serving as the de facto Library of Alexandria, the Serapeum saw rise to Neoplatanism beginning with the work of Plotinus in 245 AD when he came to Alexandria from Lyco (which could either refer to the modern Asyut in Upper Egypt or Deltaic Lycopolis, in Lower Egypt). Over the next 145 years, Neoplatanism would see itself branch off into different sects: one version taught at the Serapeum which was more religious in nature and influenced mightily by Iamblichus, the philosopher from Syria who was the biographer of Pythagoras, and a second version purported to be truer to the original teachings of Plotinus. This second version was taught at the “Mouseion” in Alexandria, an emulation of the Hellenistic Mouseion that had once included the Library of Alexandria, and was headed up by Hypatia’s father, a mathematician named Theon. Hypatia succeeded her father as the head of the Mouseion, and her school was allowed to endure even after the destruction of the Serapeum. Enter Synesius.

Synesius wasn’t someone who just sat in Hypatia’s classroom and quietly took notes. He developed a strong enough professional relationship with her that they often corresponded via letters after he left Alexandria, and it is from these letters that we’ve come to know as much as we do about Hypatia’s life. Synesius’s significant interest in alchemy led him to write a commentary on Pseudo-Democritus, those alchemical works which were attributed to the philosopher Democritus but were actually compiled by anonymous Greek authors.

All of this to say… When we look at this drawing, we are looking at a piece of the lost Library of Alexandria, something that survived the ancient world and multiple destructions of knowledge centers. It is still with us today because Synesius recorded it around the Fourth Century AD and Theodoros Pelecanos decided to make a copy of it just over a thousand years later. There is much that was lost when the Great Library was destroyed, but this is a piece we can hold onto, and it's an important one as we continue to dive into the Connected Universe. While so much knowledge and wisdom has been lost over the millennia, the universe has left us some clues to help pick up the pieces, and while the original Great Library of Alexandria is no longer with us, its scant survivors are there to help us.

Interested in learning more about the Connected Universe and gaining access to exclusive, behind-the-scenes content?

Stay connected with news and updates!

Get all the latest news, updates, and insights from author and researcher Mike Ricksecker and the Connected Universe community! Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.